“He threw it, and the Frisbee was like 10 or 15 yards ahead of me. As I kept running, I kept getting closer, and it seemed like it was floating. I caught it, and I said, ‘Wow, I like this!’”

“I was sitting there, and it was just something about the flight of that Frisbee that I thought was incredible…I just thought it was cool the way that disc flew in the air.”

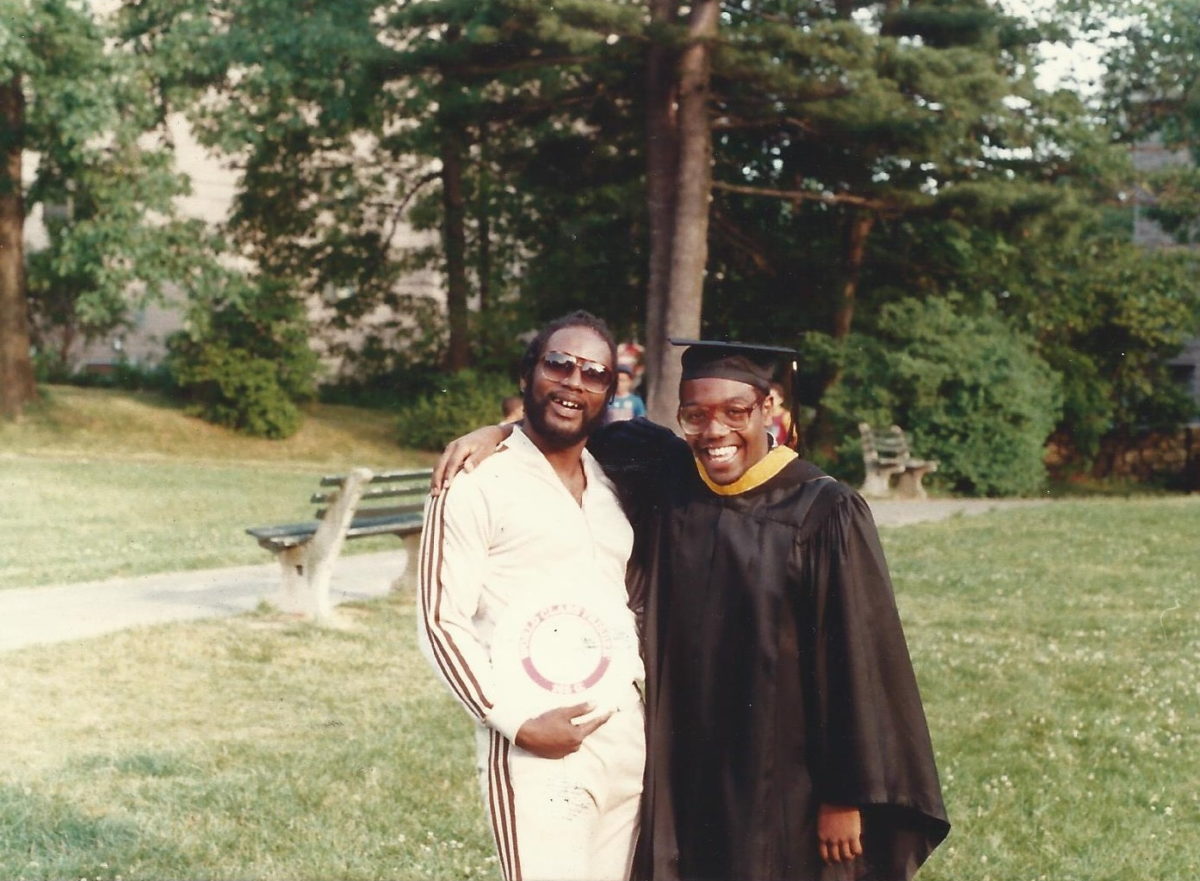

In between classes on the campus of the University of Connecticut during the late 1970s, Jerome Stallings sat and watched two guys throw a disc around with unbelievable skill.

“It was more freestyle, so they would throw it, and one would spin, catch it behind their neck…and make it bounce up and down,” described Stallings. “I asked them one day, ‘Could I throw? Show me how to do that!’”

After throwing with a variety of people and quickly adapting to the sport of ultimate, Stallings, an already active athlete at UConn, joined the school’s ultimate team. While he was in awe of the flight of the disc and loved the athletic aspect of the sport, Stallings admittedly wasn’t fully committed to ultimate initially.

“It really wasn’t important for me in my head,” commented Stallings. “If there was a game and I happened to be around, I’d play. If it was a Saturday, I was going home.”

It was near the end of his days at UConn that Stallings realized his passion for the game. While his college playing days were over, his love for the disc never died. He woke up one day and had an epiphany that would change his life forever.

“If I could get David to do this with me…then I could start a Frisbee team.”

Enter David Love, a tennis aficionado who thought ultimate was something people did at the beach.

“One day, [Jerome] invited me up to the park, and he and one other player, Larry Sturdivant, were throwing the Frisbee in the park.”

Angelic and majestic in flight, that disc captured the excitement of Stallings and Love and inspired the two young men from Waterbury, Conn., to establish the first, and so far, only all-black ultimate team: The Masters of the Bee, or MOB for short.

“When he said yes to the dress, the MOB was born,” explained Stallings.

With Love on his side, Stallings began to recruit other people he knew in the area. All of the guys were pretty good, inner-city athletes who had either played varsity football or ran track, but it just so happened that everyone he knew was black.

“It wasn’t a race thing for us. We wanted to get guys who we could play with, and all the people I knew lived in Waterbury.”

Stallings gathered the interest of many neighborhood friends the same way he was hooked: freestyle. Once everyone started learning the game of ultimate and saw how competitive it was, that’s when the fun began for the MOB. It was clear from the beginning the MOB brought a level of athleticism the local ultimate scene in Connecticut was unprepared for.

“We went to some of these smaller communities, and we would just beat up on people; it was not pretty,” admitted Stallings. “I’m not talking about in a bad way – we weren’t able to throw the disc – we just could outrun them.”

The MOB went out and dominated early on because of their commitment to the game and to each other. From the jump, the team approached practice as if they were preparing for war: running together, practicing layout drills, and doing pushups and situps. Even though their technical skills were behind a lot of ultimate players, their commitment to one another, particularly as a team of only 13 players, made the bond between them even stronger.

“We were in the middle of a game, all the time, just trying to figure out how to get the Frisbee down the field,” explained Love. “We knew we had to go from Point A to Point B, across that line, and we did it the best way we knew how.”

The grit and determination to move the disc up the field stemmed from the toughness of the players Love helped recruit. Stallings often described the guys he brought as being tough as nails.

“We had this one guy, his name was Eugene [Jackson]. He would say all the time, ‘It’s not the size of the dog in the fight; it’s the size of the fight in the dog!’” described Stallings. “We actually had guys who had that kind of spirit inside them.”

That spirit Stallings speaks of was born out of the team’s shared love for the neighborhoods they all came from, their collective introduction to the world of ultimate and the uplifting attitude everyone on the team had.

“We had another buddy named Kenny Hofler that was around since the beginning too,” added Stallings. “Those days were him showing up making sure we had enough people to be able to workout, and he was a cheerleader kind of guy too. He was pumping everybody up, and it worked out.”

One thing that especially pumped up the MOB was music from the legendary George Clinton and the Parliament-Funkadelic.

“We wants to get funked up! We want the bomb!” exclaimed Love. “We had a little square park. We used to meet there in the evening and just talk about what happened during the day, and we listened to P-Funk. We definitely were on the mothership for sure!”

While the MOB was primarily an all-black team that brought new cultures and backgrounds to the ultimate community, they were also inclusive; they started befriending and including more white players on the team.

“The first white dude to play with us, his name was Joe Proud,” commented Stallings. “That dude, if I saw him today, I could do nothing but hug him.”

He later added, “We were really inclusive. I think we would’ve played with all white guys if we had white guys in our neighborhood who were about winning a national championship.”

At the end of the day, that’s what the MOB was about: competing and winning! After taking down numerous local club teams throughout Connecticut, the MOB assessed the hierarchy and determined there were two top club teams they had to take down: the Dukes and the Tourists.

Back in the 1980s, the Connecticut State Championships were a four-team playoff featuring the state’s best club teams. During their first state championship run, the MOB proved themselves by beating the Tourists, before ultimately losing to the Dukes in the championship game, after putting up a valiant effort.

“I guess we lost; they say we lost,” grumbled Stallings. “I don’t remember losses too well; I don’t like them.”

After that initial state championship run, life started to get in the way for members of the MOB. People started having family and work obligations, and they just couldn’t afford to not work on the weekends because they would rather play ultimate for free.

“It’s a socioeconomic thing,” explained Love. “You’ve got to put food on the table to eat. If Frisbee’s not going to do it for them, they’ve got to find a way to eat!”

Recognizing the need for players skilled with the disc, coupled with the growing concern of losing players to different facets of life, the MOB approached the Tourists and proposed a merger between the two teams.

“We joined up with them, and we became Coast to Coast,” explained Stallings.

Coast to Coast, named for having team members from the east and west coasts, dethroned the Dukes as state champions two years in a row. Their crowning achievement, according to Stallings, was making it to the semifinals in the Northeast Regional Championships, placing them as one of the top 20 teams in the nation.

“This is how I’m doing the math – you can’t take this from me, and I don’t care how anybody else looks at it,” declared Stallings. “You’ve got five regions, and the four teams left in the [regional] semifinals, at the end of the day, are the top 20 teams in the country.”

Being one of the top 20 teams in the country was certainly no small feat, especially for a new team that was already giving fits to powerhouse squads like the Rude Boys.

“If you didn’t have the athletic ability to run the whole game, you were in trouble,” explained Love. “The only difference between us and the Rude Boys was just skills. They just had better throwing skills and better strategy.”

That strategy piece was where the MOB’s lack of disc skills was exposed. In the beginning, the MOB would sprint up and down the field, bringing to ultimate one of the most patented moves in basketball: the give and go.

“I’m going to put this out there: We invented the give and go [in ultimate],” proclaimed Stallings. “We couldn’t throw. So…we would treat it like how you would do the three-man weave in basketball drills, that’s how we moved the disc up the field. It became the give and go.”

While this strategy gave lesser teams problems, the Rude Boys adjusted their defense to a zone to slow down the MOB. The MOB knew what they needed to do to break the zone, but they hadn’t mastered the proper throwing skills and weren’t used to staying patient and walking the disc down the field.

Still, the top ultimate teams knew they were in a war whenever they faced the MOB, and they let the MOB know how much they were respected in the community. In the 1999 UPA newsletter article by Adam Zagoria entitled, “The Untold Story of the MOB,” Phil “Guido” Adams from the Rude Boys mentioned that if the MOB ever got the skills down, his team would be in trouble.

“I appreciate hearing those kinds of comments, but those guys were amazing,” said Stallings. “We wanted to be like them.”

While the MOB had the potential to dethrone the Rude Boys as one of the top club ultimate teams at the time, Coast to Coast ultimately broke down over a difference of philosophies.

“We were more like, ‘If we’re gonna do this, it’s gotta be like varsity basketball or football practice,'” described Stallings. “They were like, ‘Yo, let’s have a beer, then let’s go out and toss.’ By the time we got to the end, we were having issues on whose strategy was going to run the team.”

In addition to philosophical differences, some discrimination issues began to creep up on the team that combined the all-black MOB and all-white Tourists that began to rub Stallings the wrong way. Stallings knew his MOB teammates were not great handling the disc, but he wasn’t going to let them get marginalized because of it.

“They [the other players] would look at them and say, ‘Aww man, you can’t throw that good. You can just get on defense.’ And I felt like, ‘No, you’re not treating these guys like that when we just crushed y’all over the last year or two!’”

Various clashes like these led to Stallings eventually walking away from the game.

“The fight got to the point where I was like, ‘Okay, this isn’t fun anymore.’”

Praise from top teams coupled with philosophical struggles with the Tourists reflected the duality of the reception the MOB received from the ultimate community. There were some tournaments where teams would sarcastically describe them as a basketball team, while there were others that actively respected how well they played.

“Guys like the Steve Moonies would come over to us because they could recognize there was a potential there,” recalled Stallings. “After they beat us, they would say, ‘Hey man, if you work on this, you could really get better at this!’ I think because they saw the potential as athletes, I think we were received a little differently.”

Still, in the 1970s and 80s, when the country was still evolving from the era of segregation only a handful of years earlier, the MOB did have experiences where they were reminded they were black. Stallings and Love mentioned how they had a protocol whenever they traveled for games, so they didn’t draw any negative attention toward themselves when they entered new communities.

“We had to set up strategies to deal with personalities,” explained Stallings. “We had to set up strategies just to drive from Connecticut to Purchase, N.Y. We couldn’t roll down the window and have the car smelling like beer or anything else because it could’ve ended badly for us!”

Stallings recalled one incident where he and Love, in the middle of a tournament, drove Love’s father’s car from New Jersey back to Connecticut. They pulled up at a gas station and paid for their gas, but when they drove off they realized the pump never turned on.

“When we went and told the guy that it didn’t work, he said, ‘Man you guys went ahead and pumped that gas already,’” recalled Stallings.

Eventually, a police officer showed up, and the incident resulted in Stallings and the cashier each putting in an additional $5, meaning Stallings paid $15 for $10 worth of gas.

“You could tell – in their mannerisms and the way we were being talked to – they were enjoying having this control,” described Stallings.

On the field, the MOB also experienced their fair share of questionable calls, especially travels and fouls, that they felt were purposely made to prevent the MOB from winning by any means necessary, contradicting the philosophy of Spirit of the Game. However, the MOB had a strategy for that.

“When we practiced, there were no fouls,” stated Stallings. “We did not allow ourselves to have fouls because we, mentally, were making sure we were tough, so we didn’t lose it or use those rules as excuses. We had a strategy of, ‘Look, if they make the [bad] call, you respect it. It doesn’t matter. We’ll dig deeper, and we’ll whoop their ass anyway!’”

Even with the notable differences between them and other ultimate teams at the time, the MOB never had any real altercations and got along very well with teams on and off the field. Stallings credits their amicable relationship with opponents to the MOB’s ability to be cordial while simultaneously staying self-contained.

“We didn’t need the social acceptance of the environment to play,” explained Stallings. “I think it would be different if you were a black guy who was joining a white team. But for us, when I looked at my teammates, they were all like me. And the ones who weren’t like me, they had enough respect for our Frisbee ability and admiration because those guys knew we were serious about this.”

He later added, “Our experiences when we met some really awesome people who were a lighter complexion than us, who encouraged us with the Frisbee or who enjoyed our company and hung out with us, made us feel like we were included.”

That feeling of inclusion was just one example of the impact ultimate had on members of the MOB. For the first time in their lives, Stallings and Love went from being novices in something to being proficient, and they had the benefit of watching themselves go through that growth and analyze just what it was they were experiencing.

“For us to come from where we come from (socially, economically), to something that we had no idea about – we didn’t know how to understand the game, how to throw, how to catch, didn’t even know the rules of the game – and to go and to be as successful as we were, it changed our lives,” said Love.

Love and Stallings credit ultimate with teaching them a process to be successful, a process they apply in their everyday lives to give them opportunities to be successful at whatever they decide to do.

“That process that David talked about has been what we rely on,” explained Stallings. “No matter what endeavors we go into now as individual men, we apply those principles from that process.”

Being able to go through a process where you experience personal growth, gain new skills and lessons, and then get the opportunity to look back at how far you’ve come and all that you’ve accomplished is something Stallings and Love hope to pass on to more kids interested in ultimate. However, both men recognize the intentional effort that needs to be taken in order to reach kids who look like them because they understand how different the communities growing up where they grew up are to the communities of the majority of ultimate players.

“It’s one thing when you’re sitting in a big tree with a whole bunch of grass to have ultimate be something you gravitate to as opposed to sitting at a brick wall with a bunch of cars driving by,” explained Stallings. “That organic [diversity] is not going to happen without a push. [You’re] going to have to go into those communities, so they can see that it’s a viable, athletic endeavor.”

“We’re from the inner-city, so one thing is exposure,” added Love. “You’re competing against what they’re exposed to. The gap is not a skill gap, it’s an awareness gap.”

Love also recognizes the importance of going into communities and providing playing opportunities for the kids, because otherwise the kids won’t come.

“We’re not going to you; you’ve got to come to us,” he explained. “When they go to high school, there’s got to be a high school team for them. And then from high school, the colleges got to have scholarships for them to come play. So we’ve got to build that whole network, that whole link.”

Stallings also noted, while youth from communities similar to his generally gravitate towards basketball or football for professional pursuits, there can be a different approach taken with “alternative” sports, sports where an even greater value can be gained and a different endgame can be reached.

“You get that competitive release that an athletic [activity] does for you, but you also get exposure to other communities,” explained Stallings. “There’s only ~400 NBA jobs, but there’s a lot of teaching jobs, social workers and things that really help the community grow too. This sporting opportunity, ultimate Frisbee, could indirectly help more people too.”

The impact ultimate experienced when the MOB began playing is the same impact that Stallings and Love believe will continue to happen as the sport becomes accessible to more people of different backgrounds.

“When you have a multitude of different people who bring different pieces of this world, and you bring it into the sport, how could [ultimate] not be better?” asked Stallings, rhetorically. “America is still one of the greatest places in this known universe because of a multitude of different people putting in the same effort.”

“That’s what makes the spice of life – everybody brings something different to the table,” added Love. “That’s what made the MOB what we were. Within our own culture, we were diverse. We were all different, but we had one common goal, and that’s why we were the MOB.”

The MOB:

- David Blocker

- Remme Earvin

- Kenneth Hofler

- Eugene Jackson

- Michael Kidd

- David Love

- Earvin Riddick

- James Riddick

- Jerome Stallings

- Fred Stephenson

- Larry Sturdivant

- Timothy Taylor

- Glenn Williams

*Joseph Proud